Written by Ryan McGuine //

Humans produce a staggering 2 billion tons of refuse annually, and rising. When managed poorly, it has a tendency to build up and cause problems for human health — it collects in the oceans, harming sea life; clogs sewer drains, leading to floods; and gets burned openly, causing respiratory illness. This carries enormous costs. McKinsey calculated that disposing of a ton of trash by open burning or dumping into waterways costs south Asian countries $375 versus just $50-100 to dispose of properly, and the Moroccan government estimates that its $300m investment in sanitary landfills has already averted $440m in damages. Acknowledging the importance of reliable waste management, the UN chose “Responsible Consumption & Production” as the 12th Sustainable Development Goal.

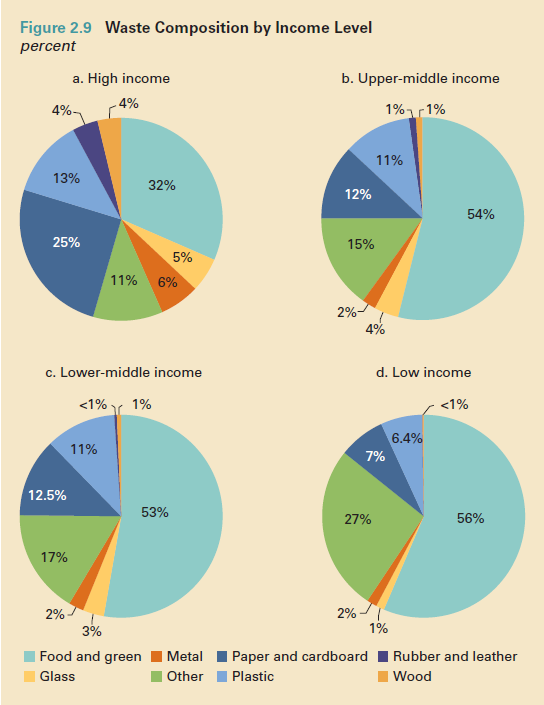

Physical waste generation tends to speed up with higher rates of urbanization, economic development, and population growth. High-income countries are home to 16% of the world’s population, but generate roughly 34% of global waste, while low-income countries account for 9% of the population and just 5% of global waste. Food waste is similar across incomes, so the difference in waste generation is mostly packaging and other non-organic wastes. However, it is not only well-being that increases waste, waste can boost well-being too. Disposable medical devices have reduced the spread of disease, and food packaging has enabled the consumption of a wider range of produce. Going forward, growth in waste generation is projected to be lower in high-income countries, since economic growth is slowest there.

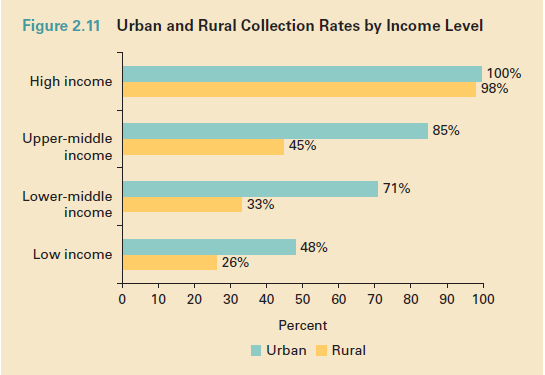

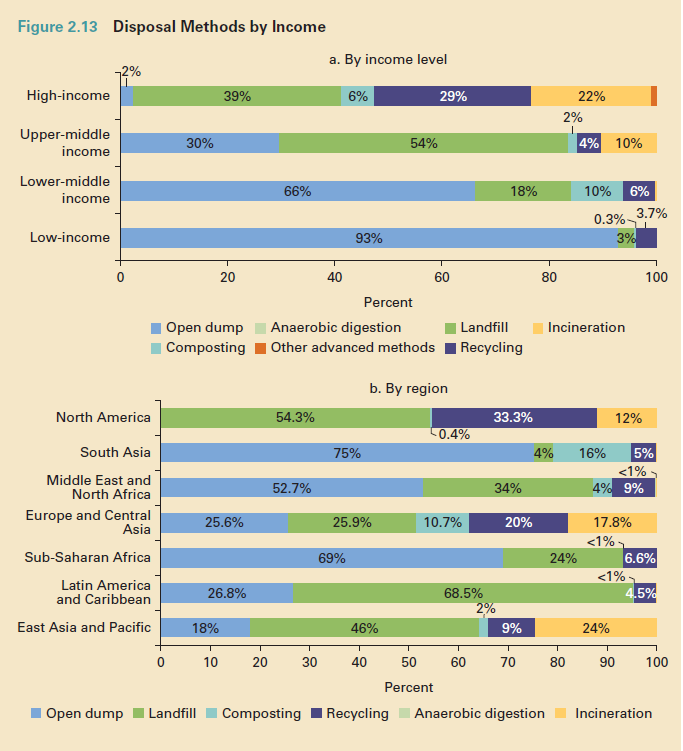

In low-income countries, door-to-door collection remains rare, and some 90% of trash is burned openly, dumped into waterways, or left on the ground. What trash does get collected is rarely sorted by those who generate it, but waste-pickers carefully dig through waste at dumps to sell to scrap dealers, potentially earning 2-3 times the World Bank’s poverty line. Meanwhile in the developed West, trash is collected from homes and offices quickly and cleanly on a regular schedule. Large trucks deliver rubbish to centralized locations, where it gets disposed of it in a manner that keeps it out of the environment. But high labor costs prevent firms from sorting what arrives, so a lot of recyclable material ends up in landfills or incinerators.

Roughly 37% of the world’s trash ends up in landfills, which bury garbage to dispose of it. One environmental effect from landfills is methane emissions. Methane, a potent greenhouse gas if unburned, is formed by the breakdown of organic materials in a landfill. Modern sanitary landfills flare off the methane, or clean it and burn it for energy, which reduces its global warming potential. Further, decomposing materials form a liquid referred to as leachate, which is harmful to human health if it reaches groundwater reservoirs. Leachate leaks can be prevented by plastic linings between layers of trash, a leachate collection system, and ongoing monitoring. Responsible environmental protection requires effective regulation, so low-to-middle income countries tend to have more landfill pollution because regulations are looser there. Landfills are the cheapest disposal method, even under strong regulatory standards — it costs about $35 to bury a ton of trash in a US landfill.

Trash incineration accounts for another 11% of global waste, and consists of burning trash in a large furnace. Most incineration facilities use the heat produced to make steam for heating or to generate electricity. Incineration is more common where population densities are higher, since space for landfills is less abundant, and adjacent buildings facilitate the distribution of steam for district heating. Incineration produces both local and global ambient air pollution. Most local pollution can be significantly reduced with air quality control technologies, but there is no way to prevent carbon emissions yet. However, whether incineration results in net greenhouse gas emissions relative to alternatives depends on how the equivalent heat, electricity, and waste disposal needs are met. Similar to landfills, environmental harm due to incineration is typically greater in countries with looser regulation. Incineration is the most expensive disposal method, costing around $300 per ton of waste.

Approximately 13.5% of the world’s trash gets melted down and turned into new products through recycling. There is a trend in recycling away from household-sorted recycling toward single-stream recycling programs, which separate recyclables from each other at centralized facilities. The convenience from single-stream recycling raises the volume sent to recycling centers, but also increases the volume of contaminated recyclables. Recycling usually has a lower energy use and global warming potential than landfills or incineration, but like all disposal methods, recycling has its own economic and environmental effects and is not always the best method. Metals and fibrous paper products like cardboard are difficult to manufacture and easy to recycle, so they should always be recycled. Others, like plastics and glass, are cheap to make and challenging to recycle, so it may be better to just throw them away.

Waste management systems in both high- and low-income countries alike are under pressure as trash volumes increase. The profitability of a waste management system depends on its success aggregating sufficient waste flows to drive business development, and efficiently organizing its supply chain. In poor countries, markets are well structured, but the aggregation bit is missing. Good infrastructure like truck and dumpster fleets, transfer stations, and sanitary landfills or incinerators help standardize collection and disposal. Additionally, since waste management is usually the responsibility of governments, it depends somewhat on levels of state capacity — the ability of a government to mobilize financial resources, and to create and enforce laws and regulations. But while good governance probably improves waste management, it is not a prerequisite for better waste management. Countries should work to build state capacity while simultaneously improving waste management.

Meanwhile, there is plenty of waste stream aggregation in wealthy nations, but the incentives are badly structured. High-income countries once shipped most of their recycling to China to satisfy its hunger for raw materials, but in 2018 China closed its borders to foreign waste, so supply now massively exceeds demand. This is a lost opportunity because recycling is not only good for the environment, but also potentially lucrative — there is more gold per pound of electronic waste than a pound of gold ore, and there are vibrant global markets for many used consumer goods. Recycling appears expensive because its full social and environmental costs are not internalized, so policies to decrease the cost of recycling relative to garbage would encourage a more circular economy. Such policies might include subsidies to the recycling industry targeting metals and fibrous paper products, programs that charge households in proportion to their quantity of waste generated, or taxes at the final point of disposal.

At the end of the day, any material or disposal method involves tradeoffs. What is clear, though, is that using resources just once is not ideal, and re-imagining the systems of manufacture and disposal is key to improving sustainability. Systems that achieve sufficient waste aggregation and market organization will naturally extract more value from waste streams — better infrastructure and state capacity will create larger, more consistent waste streams, while secondhand markets will lend circularity to waste management if the economic foundations are right. Waste management is an example of capital-intensive, risk-averse industries in which actions taken today lock in performance for decades, so getting the basics right today will be rewarded later.