Written by Ryan McGuine //

In October, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released a special report titled Global Warming of 1.5°C, an IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty — or simply SR15. The significance of 1.5°C comes from the Paris Agreement, which stated as its goal “to keep the global average temperature rise well below 2°C, and to pursue efforts to prevent a 1.5°C increase” (note that the sum of the current country-submitted targets that provide the foundation of the Paris Agreement is only enough to prevent about 3°C of warming, and most countries are not even on track to meet their targets). The compilation of SR15 involved 91 authors from 40 countries, over 6,000 cited references, and 42,001 expert and government review comments.

The IPCC is a UN body of scientists that writes reports in support of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the UN’s main treaty body on climate change. The group writes major “assessment reports” periodically, which provide comprehensive reviews of the latest climate science, as well as numerous shorter, more topical “special reports” in between. The IPCC does not does not carry out any original research, but rather summarizes the available climate science literature.

Before diving into the report, it is useful to conceptualize climate change, since it is a nebulous phenomenon that is remote from most people’s daily lives. The climate is an example of a “global public good.” As such, it tends to be undervalued by individual actors, and its preservation requires overcoming the “collective action problem.” Since carbon dioxide — the main pollutant that affects the climate — is a global ambient pollutant, a ton of carbon reduced in one place has the same benefit as a ton of carbon reduced anywhere else on the planet. Thus, it is in the best interest every country to reduce its carbon emissions and encourage others to do the same.

However, even though self-interested countries have some incentive to reduce their carbon emissions, in almost no case do the negative externalities associated with carbon production entirely outweigh the benefit to society associated with fossil fuel consumption. For developing countries in particular, the value of carbon emissions mitigation is quite low. Therefore, any realistic emissions projection should allow for low- and middle-income countries to increase their carbon emissions in the short term.

Now, on to SR15. One thing the report does is establish the link between some of the unusual phenomena observed today and the warming observed since pre-industrial levels — about 1°C. The IPCC suggests that this increase is already playing a role in more extreme weather, rising sea levels, and diminishing Arctic sea ice. Many single events have been shown to have been made worse by climate change, and the frequency of extreme weather events is expected to continue to increase going forward.

SR15 goes on to highlight some of the important differences between the impacts of a 1.5°C scenario and a 2°C scenario, and they are stark. For example, by 2100 global sea level rise could be nearly 10 cm less, the likelihood of an Arctic Ocean free of summer sea ice would be once per century compared to once per decade, and coral reefs would decline by 70-90% compared to over 99%. This analysis makes clear that even if 1.5°C of warming cannot be prevented, any emissions mitigated still makes a difference — staying below a certain threshold does not guarantee certain things will not happen, and passing a certain threshold does not guarantee that certain things will. What is certain is that the further beyond any threshold the temperature gets, the more dramatic the effects will be.

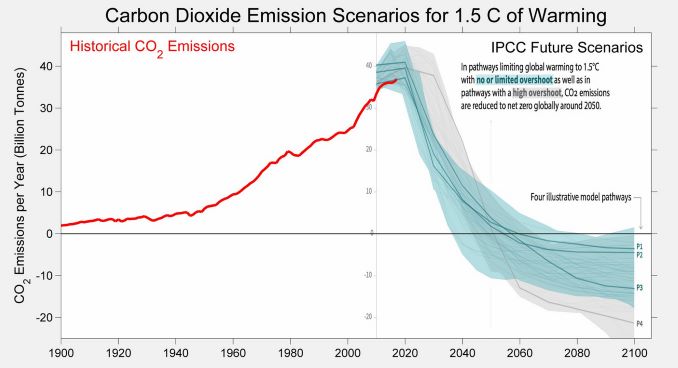

In order to prevent 1.5°C, SR15 says the world must begin reducing carbon emissions beginning in 2020, and reach net-zero carbon emissions between 2040-2055 (see chart below). To put this in perspective, annual growth in carbon emissions has been slowing recently, and some advanced economies have even seen emissions level out in recent years. However, in 2017 global emissions still rose by about 1.6%, and there is little evidence that the world is on track to reach peak emissions in 2020, let alone begin decreasing emissions, given business-as-usual.

Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2018), Special Report 15

Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2018), Special Report 15

Achieving a 1.5°C scenario would require “rapid and far-reaching transitions in energy, land, urban and infrastructure (including transport and buildings), and industrial systems.” The prevailing wisdom on how to achieve serious global decarbonization is “decarbonize electricity, electrify everything.” The power sector, which has the advantage of being responsive to relative fuel pricing, is close to being on track to meet the IPCC’s prescribed 70-85% of global electricity from carbon-free generation by 2050. Electrifying the rest of the economy turns out to be the much more difficult — few viable electrical alternatives exist today for industrial boilers, or airplanes and cargo ships. Finally, it is important to keep in mind that preventing 1.5°C, and likely even 2°C, is impossible without technologies that remove carbon dioxide from the air, regardless of the how successful carbon mitigation efforts prove to be.

The report estimates that the discounted cost of cumulative damages by 2100 could be $54 trillion under a 1.5°C scenario, and $69 trillion under a 2°C scenario. Any warming warming beyond 2°C will end up costing society even more than $69 trillion. These costs represent the estimated rise in spending on storm damage, healthcare, reduced crop yields, and many other consequences of climate change. While SR15 includes no estimate of the costs required to achieve the necessary climate mitigation to remain below these targets, they are certainly less than those of doing nothing.

The actual costs of damages are probably much higher than these estimates, though. For example, future values of money always include a discount rate, the value of which can significantly affect estimates. While this has long been contested with respect to climate change, conventional values of social discount rates are probably too high. Additionally, communities suffering from extreme poverty are likely to bear a disproportional amount of the costs associated with climate change. Subsistence agriculture and very small-scale commerce are the dominant professions for much of the world’s poor, and climate change threatens to make their way of life impossible. While the actual loss in monetary terms may be quite small, there is no easy way to value the loss of one’s entire livelihood.

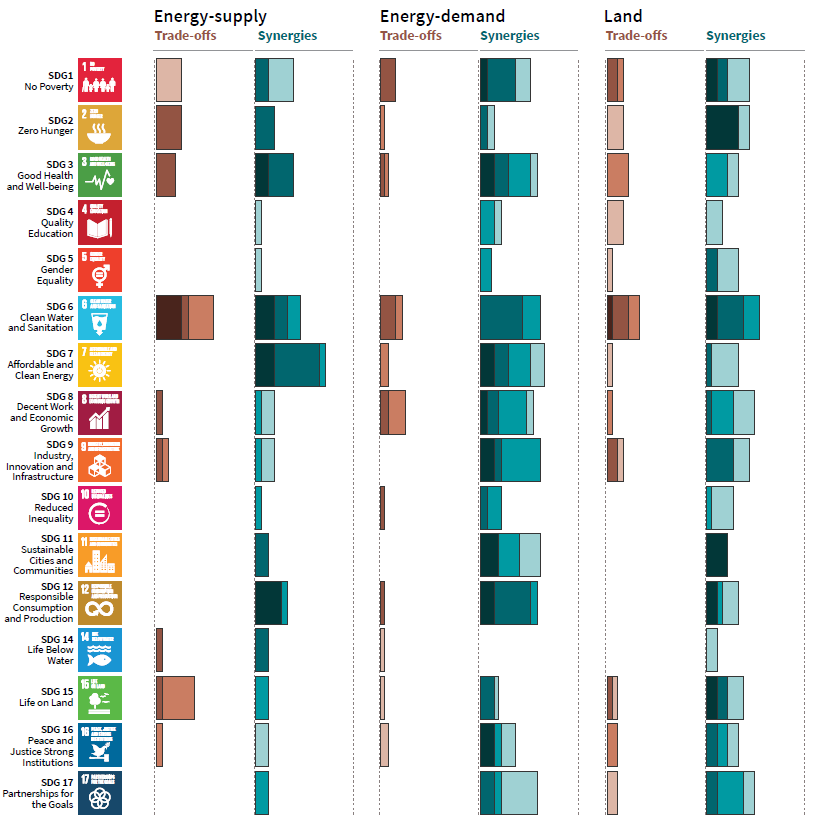

The report has mixed implications for global development. On one hand, developing countries face the fundamental injustice of climate change — that the populations least responsible for historic carbon emissions will suffer the most in the future. However, it must also be mentioned that higher levels of energy consumption are highly correlated with higher levels of income, and higher incomes enable easier adaptation to climate change. Thus, while increasing energy consumption almost invariably leads to higher carbon emissions, the capacity of low-income countries to adapt to changing weather patterns increases with higher levels of energy consumption. These trade-offs are acknowledged in SR15, and summarized in terms of the Sustainable Development Goals by the graphic below.

The potential positive (synergies) and negative (trade-offs) effects of mitigation options for reaching 1.5C on each of the sustainable development goals. The mitigation techniques are split into three sectors: energy supply, energy demand and land. The total length of the bars represent the size of the positive or negative effect, while shading shows the level of confidence (light to dark: low to very high). Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2018), Special Report 15 Summary for Policymakers

The potential positive (synergies) and negative (trade-offs) effects of mitigation options for reaching 1.5C on each of the sustainable development goals. The mitigation techniques are split into three sectors: energy supply, energy demand and land. The total length of the bars represent the size of the positive or negative effect, while shading shows the level of confidence (light to dark: low to very high). Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2018), Special Report 15 Summary for Policymakers

To summarize, there is slim chance that the world will prevent 1.5°C of warming, since getting there would require a concerted effort by every sector beyond what most suspect is realistic. Industrialized countries have huge amounts of carbon-intensive infrastructure installed today and are unlikely to want to retire it early, and one of the surest pathways to adaptation for developing economies is to increase energy consumption. Passing the 1.5°C mark will have serious consequences for the natural environment, which will impose real costs on society due to stronger storms and changing weather patterns. That does not mean that taking action is futile, though — the report clearly establishes that the combination of investment in low-carbon R&D and rapid deployment of low-carbon technologies can help prevent warming, and that any warming prevented is worth pursuing.